Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo was born on May 11, 1871 in Granada. He grew up in the shadow of the Alhambra, walking through the narrow streets of the Realejo neighborhood, lived in a Moorish house, was the son and grandson of artists, and his father had a studio of Nasrid jewelry, to which this Andalusian artist was linked all his life. These influences that Mariano assumed as a child and the creativity of his family, inspired him throughout his life and are reflected in all his work. He was from Granada, a man of great sensitivity and freedom, eager to break the mold and turn expectations around, an artist, set designer, photographer, designer and inventor who transcended in history.

Fortuny Madrazo lived in Paris and Rome, until he moved to Venice at the age of 18, where he settled and lived for the rest of his life. He was a tireless artist, and although painting was his main activity, he did not understand art as an isolated discipline, but was trained in other modalities and combined all learning, so that all were represented in his works. A complete artist, photographer, designer, set designer, inventor?

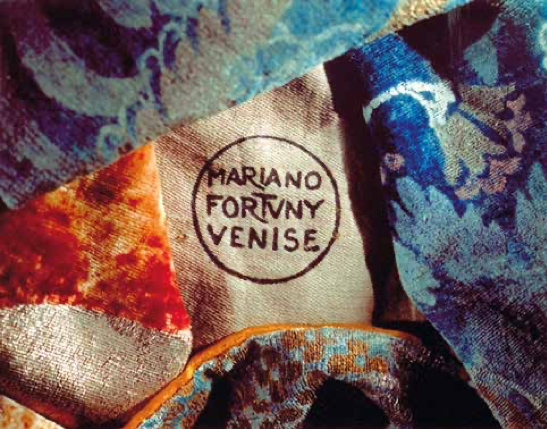

Fortuny and textiles.

Outside of painting, his role as a stage designer in the theater stands out. When I created a set design, I added knowledge of photography, painting, sound, light and textiles. It was in the theater where he began his career as a textile designer. One of his innovative contributions is the recovery of natural silk, cotton and linen fibers, although he also experimented with the first chemical fibers that appeared. He designed costumes, worked with silk taffeta from Japan, used satin, plain silk velvets for medieval and Renaissance-inspired garments and Naples grosgrain.

Fortuny gave special importance to the choice of the fabric, being very meticulous in the quality of it, he liked to buy the pieces raw, avoiding that the raw materials had suffered any kind of manipulation.

The innovation of her designs caused the dresses she designed for the theater to become fashionable designs that people wanted to have.

The Delphos, its icon.

Fortuny was a great researcher, and that led him to invent dresses, one of them, the Delphos, became his great work. Its origin goes back to a visit of Fortuny to Greece, where he was impressed by the Delphi Auricle, he spent two years trying to find the technique that would allow him to make the pleats of the fabric, developing a new pleating technique performed in two phases. “On the damp canvas, with a brush, she applies egg white albumen, just as her father used to do in his oil painting on canvas; this albumen works as a fixative element of the pleating, enhances the brightness and gives the fabric a ductile and soft behavior. Subsequently, the fine pleating is carried out in two phases: vertical and wavy. ” The Delphos” became a fashion icon, and is still being produced today.

Fortuny Upholstery

To design your fabrics, he liked to use cottons, imported from London and produced in India, or some thicker ones of French origin, with which he made his twill hangings. These twills replaced heavier fabrics that were used until then in the theater. On the other hand, Fortuny began to use Egyptian cotton, known as jumel, to make some garments in which it was convenient to emulate the lightness of silk, but not its shine. He was also a revolutionary in the use of color, he was credited with secret formulas of the ancient dyers or unknown materials, he experimented with all kinds of dyes, from the vegetable world, such as indigo or palo de campeche and saffron, or from the animal world, such as cochineal or múrex. Within his textile career, he will also work with inorganic dyes such as metallic oxides and others brought from Brazil, India, Mexico and Chile.

Curiosities:

It is said that the day after he died in the city of Venice, the waters of the Venetian Grand Canal were dyed in fabulous colors to the astonishment of visitors and locals alike. The first explanation that would come to mind today would be an artistic action, but this was not the case. Apparently someone – Henriette, the widow, was pointed out – had thrown away the pigments used by the recently deceased painter, in an involuntary but lacerating metaphor of the oblivion in which his name would end up buried.

Recent Comments